- The French Army in the Korean Conflict

The official announcement of the creation of a brand new unit intended to be sent to Korea under the name of “Bataillon Français de l’ONU” or “BF/ONU” soon nicknamed the “Boeuf/ONU” (Beef UNO), was made by press release and internal mail dispatched to all barracks, in France or in the French Associated States, and reached even French occupation forces in Germany.

The volunteers soon joined the Auvours Camps (near Le Mans), where the men were physically and psychologically evaluated. Some of them were “civilians”, coming from the “reserve” (Home Guard), but this term is in this case an understatement, for most of these men had already seen war. Most were in Libya, in Tunisia, in Italy; they had fought in France with the army or in the resistance, then in Germany in the last months of 1945. Some of the men in active service even fought desperate fights against Japan in Indochina. Some of the younger ones already had been touring Indochina after the Second World War. Therefore, though a call for both “reservists” and men in active service was made, all the volunteers were, in fact, cold-blooded professionals who knew very well what war could be. Usually in their twenties, they were just a little bit older than the men in the US Army. They were experienced men who knew the meaning of duty, and shared the same political thoughts and aims: anticommunism, solidarity with the American and British allies, assistance to a weak Korean Republic assaulted by the Soviets, or for some officers, the exciting perspective to be the first peace soldiers under the UNO’s flag [27].

As Kenneth Hamburger points out, the decision to send a French battalion to Korea represented a risk for the French government because if there were a failure in combat operations, all efforts to obtain the US military assistance in Europe and in Indochina would be in vain ([1], p. 65). Therefore, the BF/ONU was a fake one, a kind of fiction, which was made up of experienced volunteers and did not reflect exactly the situation of regular units, as the French Army was mainly a conscript army, though with a core of experienced active service men. Consequently, the BF/ONU did not reflect at all the situation of an average French Army battalion made up of a core of active servicemen and sometimes reluctant conscripts [28].

Leaving Marseilles on October, the BF/ ONU disembarked at Pusan on November 29, just as the Chinese offensive began to sweep General Macarthur’s forces. Involved in battle operations at the end of December, after a short drill, the French battalion was integrated to the 2nd US Infantry Division “second to none” [29] and assigned to the 23rd US Infantry Regiment. The 23rd Regiment’s Commander Colonel Paul L. Freeman Jr. accepted including the French battalion in his unit, though the French were commanded by General Ralph Monclar [30], an old foreign legion officer, who had displayed the utmost gallantry in Verdun in 1916, in Narvik in 1940, and in Ethiopia in 1941. General Monclar even had abandoned his stars to become a fictive lieutenant-colonel, in order to command the French battalion, for no general can be in command of such a small unit as a battalion, and was eager to serve in the first UNO’s Army, though he was already 60 years old.

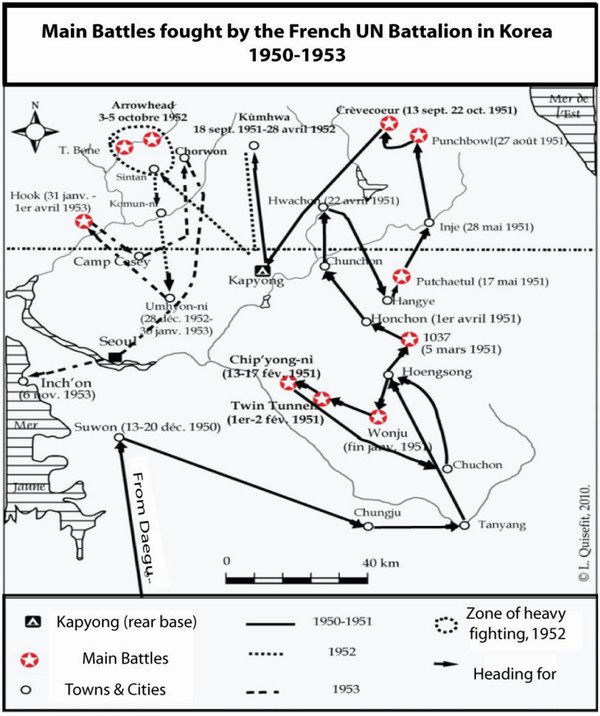

The French battalion participated in all the decisive battles of 1951, especially Wŏnju, Twin tunnels, Chip’yŏng-ni [31], 1037, and Crèvecœur (Heartbreak Ridge).

The French displayed not only gallantry and stubbornness but also a challenging spirit. They had volunteered to fight, and they did. They displayed initiative and willingness to sacrifice, along with great pragmatism, though sometimes lacking discipline, at least according to US Army standards.

One anecdote is significant. During the bitter cold of the Korean winter, the French made fires to warm themselves and to soften the frozen ground in order to dig it. These lights alarmed the 23rd Regiment officers, anxious about possible enemy attacks. When Colonel Freeman told Monclar to put these fires out, the French general replied that if the Communists knew where the French were, they would attack the French battalion, and then the French could kill them… [32].

In Wŏnju, during the first battles of 1951, two platoons of the BF/ONU launched bayonet charges against the enemy, in their own sector. Though the French were firing and hurling grenades, the rush of shouting men, with bayonets fixed, through unprepared Korean and Chinese units scared the Communist troops. Lieutenant Lebeurrier’s platoon ran through a whole North Korean company and routed it. “This spirit of the bayonet” was what General Matthew Ridgway wanted in the entire Eighth Army, and he used it to inspire US Soldiers, telling them to follow the example of the French ([1], p. 94). In fact, the Turkish Brigade and the Belgian battalion sometimes conducted bayonet charges during the Korean War. The BF/ONU’s action at Wŏnju, however, came at a timely moment, just when Ridgway wanted to improve the morale of the Eighth Army.

A few weeks later in Chip’yŏng-ni (February 13–15, 1951), the French battalion and the 23rd US Infantry Regiment fought a decisive battle against the Chinese army. For the first time, the Chinese volunteers encountered hardened troops, well entrenched and protected by the first barbed wire network installed around the UN army positions. Air supplies and tactical support, and short and long range artillery shelling helped to successfully resist the communist force: at least five Chinese Infantry Divisions attacked the Allied forces in Chip’yŏng-ni. As some UNO positions were being overwhelmed by the enemy on the afternoon of February 15, the pocket was eventually rescued by units of the 5th Cavalry Regiment (Task Force Crombez) under heavy fire and stubborn Chinese opposition. The Chinese finally retreated from their advanced position inside the perimeter under the pressure of napalm bombardment and counter-attacks. The arrival of Task Force Crombez ([1], p. 204–207) with about 20 tanks was determinant in the final victory.

After the fight, Lt. Colonel John H. Chiles [33], commanding the 23rd Regiment gave an interview to American journalists about the recent fighting and explained how he had fought against five Chinese divisions alongside the French during the three days' siege of Chip'yong-ni.

He said that the “French were beyond praise”, that they always hold on their positions, always captured their targets and never abandoned taken ground [34].

The success of the Chip’yŏng-ni battle was welcomed as a major victory for at least two reasons. First, it stopped the Chinese offensive and permitted the UN forces to soon after launch a counteroffensive to regain the ground lost in January. Second, it concealed the reversal which occurred in Hoesŏng, where the Dutch battalion attached to the 38th Infantry Regiment suffered heavy losses at the hands of a communist commando who killed most of the commanders of the Dutch unit, along with the dramatic losses of about 2000 men experienced by allied troops in the area [35].

The gallantry of the men of the 23rd Regiment, and their French brothers-in-arms was also a useful propaganda tool in order to boost a fighting spirit deeply damaged by the Chinese winter offensive.

Due to the rapid mutations of the Korean situation, and because of the war conditions, the French and the 23rd Infantry Regiment, having thus gained a reputation of bravery, were sent to most of the hot spots on the frontline.

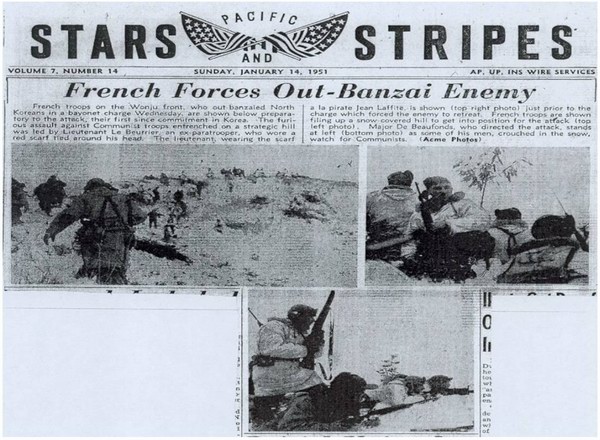

Replaced at the end of 1951, then again in 1952 and at the beginning of 1953 by new men and officers, the BF/ONU gained the reputation of an elite fighting force which never abandoned its positions. In Wŏnju, the French even “out-banzaied the enemy” (sic) [36]. Laudatory articles were written about the “Frenchies”, such as “French Bayonet Charge Route Red near Wonju”, reported by the Pacific Stars and Stripes [37] (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Hard battles were also fought in 1952, at the T-Bone and near the Punch Bowl, at Arrow Head (Hwasalmŏri-koji), White Horse (Baengma-koji), Majuni, etc. (Figure 3).

At Arrowhead in October 1952, the engineer platoon, installed at the foot of hill 281, was almost completely annihilated by the red assault, in spite of a fierce struggle, just as the engineers of the first battalion had suffered dramatic losses in Chip’yŏng-ni.

The French battalion is one of the most decorated units of the Korean War. Indeed, the battalion by itself received not only French military citations and medals, but also two Korean Presidential Citations, two Distinguished Unit Citations, as well as other medals. [38]. Regulars, NCO’s and officers also got silver and bronze stars, French Croix de Guerre (The Cross of War), and other medals and distinctions.

During an address to the US Congress in May 1952, General Ridgway said of the French battalion: I shall speak briefly of the 23rd United States Infantry Regiment, Colonel Paul L. Freeman commanding, [and] with the French battalion… Isolated far in advance of the general battle line, completely surrounded in near-zero weather, they repelled repeated assaults by day and night by vastly superior numbers of Chinese. They were finally relieved….I want to say that these American fighting men, with their French comrades-in-arms, measured up in every way to the battle conduct of the finest troops America and France have produced throughout their national existence [39].

Figure 1. Front page of the Stars & Stripes Pacific Edition, January 1951.

Figure 2. Stars & Stripes Pacific Edition article, January 1951.

Figure 3. Map of the main battles of the French Battalion.