- Vanishing Memories of War

“Old soldiers never die, they fade away”. In 1993, the South Korean government decided to build a war memorial intended to transmit the history of the wars fought in Korea, in order to teach this history to the young generations, because the memory of the Korean War was vanishing with the men and women who had fought or were victims in the conflict.

In Korean minds, the Korean War holds the same traumatic place as the American Civil War for Americans and the two world wars for the Europeans. It was a national disaster which produced long-lasting trauma. Beyond the human and material losses, the 1953 armistice fossilized the division of the peninsula, and severed the relations of 10,000 families from their relatives in the North.

The Chŏnjaeng Kinyŏm-gwan (War Memorial) [40] in Seoul is not only a history museum, but also a sanctuary of national defense [41], and the names of the soldiers killed in action are written on the walls of the Memorial. The names of the men from 16 countries, who answered the United Nations’ call and were killed in action in Korea, are written on the walls of the galleries outside the Memorial.

Though Korean schools often arrange visits to the Memorial, the teachers barely explain which countries were involved and pay no particular attention to the small contributors. The Memorial is indeed very huge, and all the wars suffered by Korea, from antiquity to our days, are usually presented in a heroic and nationalist way.

The War Memorial was built to commemorate actors and victims in the wars which led to the modern Korean nation-state, focusing mainly on resistance against Japan and the Korean War itself. The purpose of the museum is also to educate future generations by collecting, preserving, and exhibiting various historical relics and records related to the many wars fought in the country, without saying, from a South Korean perspective, sometimes according to nationalist views, which often produce clichés. These stereotyped approaches are sometimes far from true history as seen in contemporary literary and historical materials, but they praise heroism and fighting spirit.

Other French “places of memory” [42] exist in Korea, and especially the French monument in Suwŏn, devoted to the memory of the 288 men killed in action, including the 18 missing in action, both Frenchmen and South Korean KATUSA [43] attached to the battalion. The memorial was constructed in October 1974 by the South Korean Ministry of Defense, “in tribute to and in memory of the French armies who came here as the crusaders of justice, to protect the security and freedom, made remarkable military gains, and died in the Korean War” [44]. Though the monument was restored in 2001 and developed as a memorial combining French and Korean cultures, it is deteriorating quickly, but had been renewed for the 60th anniversary of the Korean War. It is, however, used only once or twice a year for ceremonies.

In Tongchŏng-myŏn, in the province of Hongchŏn, stands the statue of the medic Major Jules Jean-Louis, who died out of mines while trying to assist two wounded Korean soldiers lying in the same minefield. This statue was built through the efforts of one of his former interpreter and medical assistant, Dr Kim Yang-Hŭi [45], and the support of various French and Korean associations. The statue was erected in 1986, during the commemoration of the centennial of the establishment of the relations between France and Korea. With General MacArthur’s statue in Inch’ŏn and the one of General Walton Walker (unveiled on June 2010), this is now only the third statue of a foreigner standing in Korea. Nonetheless, this statue stands in a remote place in the countryside, and very few people come to pay homage.

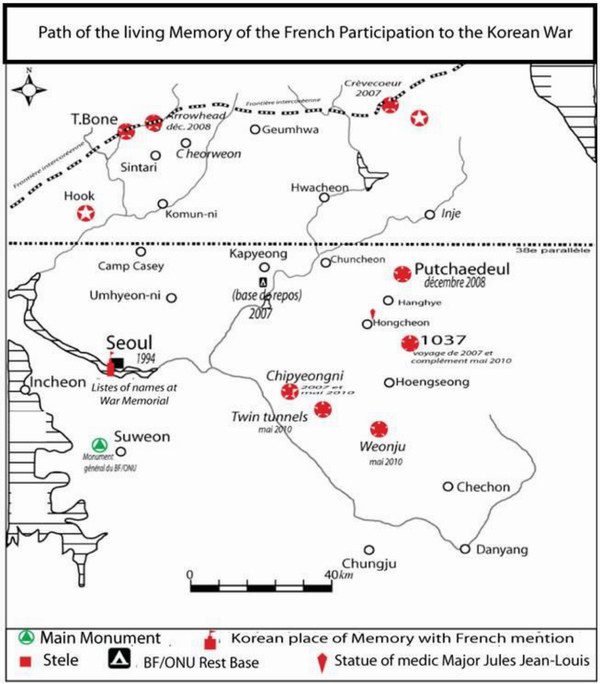

These monuments were not enough. The French battalion had fought or died in many places throughout South Korea (see maps). Since most of the Koreans, especially the young generation, know nothing about France’s participation in the conflict, and because the veterans, as well as the people who suffered from war, are vanishing—more than 60 years after the beginning of the Korean War—it was necessary to do something not only to preserve the memory of the participation of the French Army in the conflict, but also to build a new comradeship between the two countries.

Thus, came the idea of a “Path of the Living Memory of the French Participation in the Korean War” to be built in all places where the French battalion had fought. The project was promoted by the French Embassy and military attaché, which spared no efforts to persuade both Korean and French authorities to participate in the project. The French Korean War Veterans Association (ANAAFF/ONU), The Korean Ministry for Patriots and Veterans, the Korean Veterans Association, The French Ministry of Defense, and some private donators were also involved in the project.

A collection of steles and monuments, explaining briefly the conditions of the fight and the French Army’s participation in the war, under the motto “For Freedom” (Pour la liberté, Jayu-rŭl wihayŏ) (Figure 4), written in the three languages, with the UNO, French, South-Korean and US flags, the insignia of the French battalion and also the badge of the 2nd US Infantry division, was erected.

Figure 4. The Puchaetŭl Monument.

For instance, the monument at the entrance of the Puchaetŭl valley, near Inje, reads as follows: “Here, at Karisan, Chauni and Puchaetŭl, in May 1951, the volunteers from the United Nations’ French battalion assigned to the 23rd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, 2nd US ID, fought side by side with their Korean brothers in arms. The Engineer Platoon sacrificed themselves” (sic) [46].

In 2007, monuments were inaugurated in Pusan (UN Cemetery), Kapyŏng, Twin Tunnels, Chip’yŏng-ni, Hill 931-Heartbreak Ridge (Crèvecoeur). Afterwards, in December 2008, the monuments at Puchaetŭl and Arrowhead were unveiled. In 2009, only a small group of veterans travelled to Korea in order to prepare the ceremonies of the 60th anniversary of the beginning of the conflict.

In 2010, steles were erected at Wŏnju, Hill 1037, etc. (Figure 5). Some sites received new monuments in a second phase. In Puchaetŭl, where the French had positioned themselves on the hills, on a difficult ground, the monument has been installed in the valley. In the same way, the monument of Arrowhead was built on a hill facing the former positions, the sites being now inside the Demilitarized Zone (Figure 6).

Moreover, General Oh, the then commander of the South Korean 2nd Army Corps, had on his own initiative erected a commemorative monument in remembrance of the sojourn of the French battalion in Chunch’ŏn.

The aim to these steles and monuments is to allow ordinary people (except for the particular case of monuments still in military zones) to see, read and learn about French participation in the Korean War.

In Chip’yŏng-ni, the old school of this small town was used as a command post by the battalion Commander General Monclar. This school still stands in the city, and pupils visit the site every year. In other places, trekkers and walkers can see the commemorative monument while walking in the countryside or hiking in the hills.

School visits are encouraged. The pupils of the French high school in Seoul (Lycée Français) were associated to the ceremonies of the Arrow Heads monument inauguration in 2008.

Figure 5. Map of “The Path of Living Memory” stations.

Figure 6. Arrowhead stele, facing the DMZ line